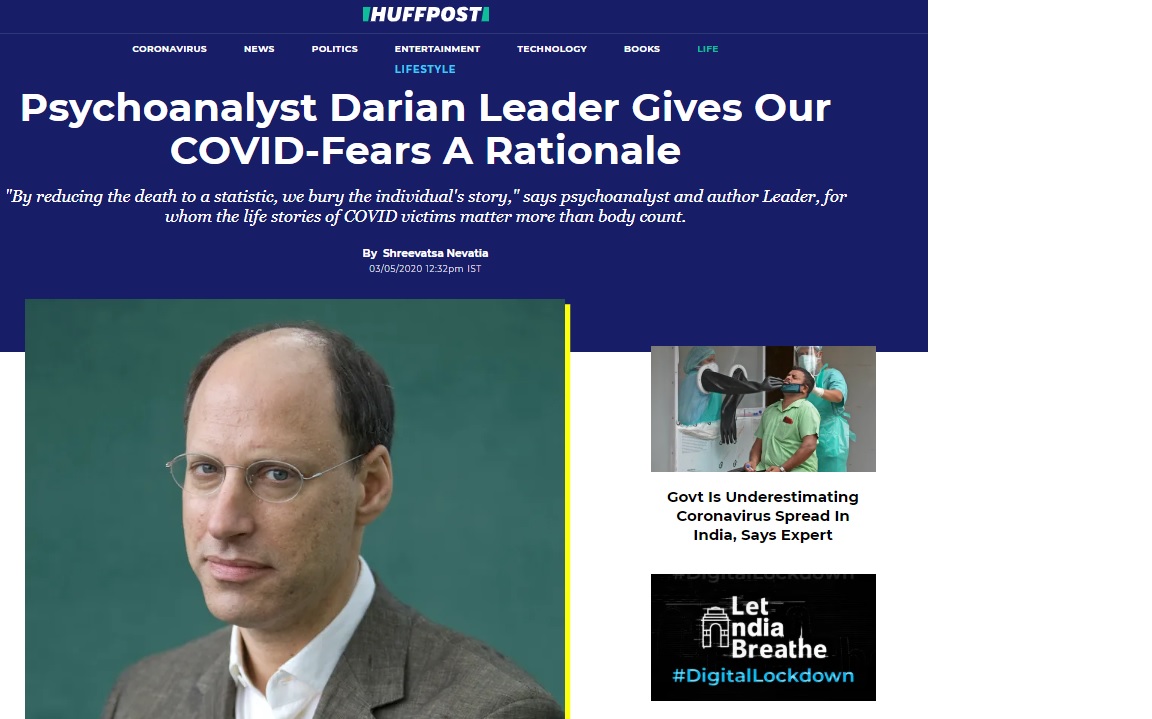

In the 1950s, researchers at Edinburgh University conducting a study into sleep concluded that there was little difference in sleep time between using a well-sprung mattress and a wooden board. Try telling that to retailers of £500 multilayered mattresses. For sleep, as the psychoanalyst Darian Leader reminds us in his richly researched and entertaining Why Can’t We Sleep?, has been commodified: it’s big business.

In the 1950s, researchers at Edinburgh University conducting a study into sleep concluded that there was little difference in sleep time between using a well-sprung mattress and a wooden board. Try telling that to retailers of £500 multilayered mattresses. For sleep, as the psychoanalyst Darian Leader reminds us in his richly researched and entertaining Why Can’t We Sleep?, has been commodified: it’s big business.

Before advancing reasons for insomnia, and why one in three adults complains of sleep difficulties, Leader delves into the history of sleep research and competing theories about why we sleep, which have culminated in a remarkable inversion of concern: a shift from anxiety causing problems with sleep to the present, where the lack of sleep leads to anxiety.

Some judgments, though, have resisted change. In the 1960s the eight-hour “ideal” sleep was shown by the researcher William Dement to be a “fallacy”, yet today, argues Leader, sleep experts promote eight hours as the desired gold standard – almost as a human right.

Leader rolls his eyes at the zeitgeist of the “new science of sleep”, with its notions of sleep as a self-help curative for ailments ranging from dementia to unhappiness, all achievable “with sensitive temperature control and software that will tailor the environment to their unique circadian rhythm”.

There’s no consensus on the point of sleep. But there is agreement that it is a time for the processing of memories internal body clocks’ association with sleep cycles have long been recognised, but sleep wasn’t always undertaken in one unbroken block. The historian Roger Ekirch argued that prior to the 19th century sleep was biphasic – taken in two parts with an hour or so in between when the person was awake.

With the Industrial Revolution, maintaining nonstop production lines necessitated shift work and changes to patterns of sleep. Today, businesses’ co-option of sleep in enhancing productivity is illustrated by firms such as Aetna offering $25-per-night rewards to employees (monitored via sleep trackers) who manage 20 nights of sleep for seven hours or more in a row.

Goal-oriented sleep research becomes problematic when it approximates the maxim: “What the thinker thinks the prover proves.” We might be inclined to look more closely at conclusions drawn by Nathaniel Kleitman’s classic 1939 study Sleep and Wakefulness, says Leader, when made aware that his university research “was heavily funded by corporate sponsors keen to engineer more productive workers”.

Leader also questions the value of extrapolating into the real world conclusions drawn from experiments carried out in unnatural environments. Contemplating the validity of experiments with patients isolated overnight in sleep clinics using EEG, he observes: ‘They don’t have sex with a bedfellow or masturbate, and yet this entirely artificial subject is the one we expect to give the real facts about sleep.”

… [Click here to read the rest of this article on the Guardian Site]

Darian Leader is speaking in Bristol at the CFAR/Bristol University Lecture Series on the 22nd of June 2019.

–

–